|

Organize your own workshop!

Once you've made a microscope, you might consider sharing what you've learned by organizing a workshop. I started running in-school workshops for elementary school teachers after contacting one of my own kids' teachers to ask if this seemed of interest to elementary school teachers. The feedback was great – the microscopes were an easy and inexpensive replacement for dusty old microscopes that only one person could look into at a time.

Below are some tips for anyone who'd like to run their own workshops, based on our experiences so far. Kenji's original Instructable is of course a great resource – I recommend reading that first. What's below assumes that you've already seen the Instructable, which includes a full parts list. |

|

|

Overview of our workshops:

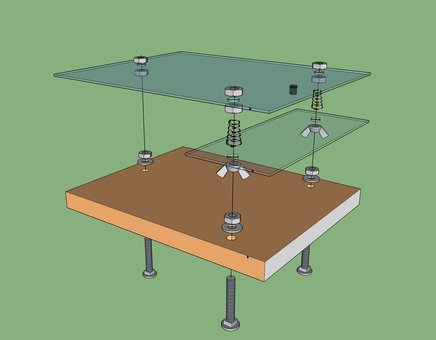

I pre-cut the plexiglass, drill the holes in the wood and plexiglass, and glue in the lenses, and the workshop participants then do the rest of the building. Workshops for teachers run 90 minutes, and three things happen:

|

|

|

Preparation of materials:

Just before the workshop:

|

|

|

At the workshop:

|

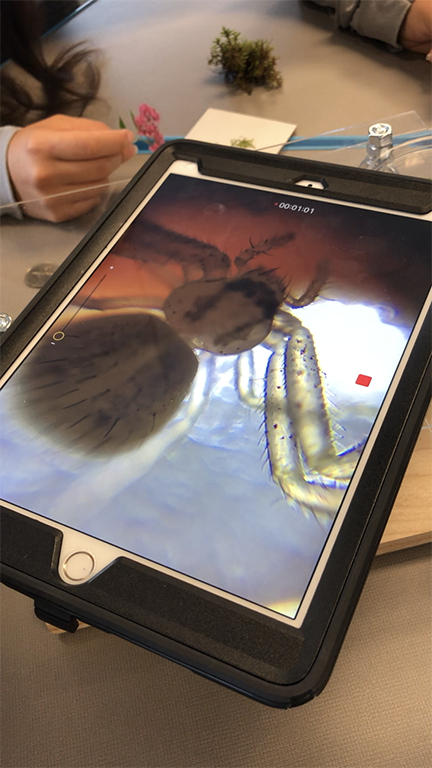

a resourceful teacher examining her own hair in a microscope she just built

|

|

After the workshop:

|

|